“Those were times when women wore saris, salwar kameez, pherans—basically anything they wanted,” she said.

By 1990, however, everything had changed.

“I returned to college in the middle of 1990. There were no Kashmiri Pandit teachers or students, and all the Muslim girls were wearing abayas—it was unrecognizable…a sea of black,” said Mattoo. Hers was one of the few Kashmiri Pandit families to not flee after the start of the insurgency in the Valley in 1990.

A police constable has stood guard at her house ever since the summer of August 1991, when her husband, an Indian Forest Service (IFoS) officer, was attacked by militants on his way to the dentist. He was saved by his Muslim driver and Sikh neighbours.

“Now, all of Srinagar is a sea of black,” Mattoo rued. “Earlier, when women were coerced, they resisted it—after a few months, they stopped wearing the hijab…Now, they are all wearing it voluntarily. For those of us who witnessed women’s stout resistance to the hijab in the 1990s, it is an odd sight.”

But it is not just women’s attires that have changed irrevocably since the heady days of pre-militancy Kashmir. The over-three decades of bloodshed, untellable violence, and conflict that have followed since have fundamentally transformed what it means to be a Kashmiri woman—politically, sociologically, economically, and psychologically.

For many years, the experiences of Kashmiri women have been refracted through the prism of a bloody conflict. In the larger public imagination, Kashmiri women have been given space, so long as they fit the role of grieving mothers, martyrs’ wives or rape victims.

But as Shazia Mallik, a professor of women’s studies at Kashmir University argues, “Conflict, although a prominent one, is just one of the factors in a woman’s life.”

How did years of conflict change women’s role in society? With the state on the one hand, and the revivalist militants on the other, what were the survival strategies employed by women? How did they navigate the violence of the 1990s and early 2000s? And what do they desire now?

As the assembly elections in Jammu and Kashmir conclude after a democratic lull of a decade, ThePrint traces the traumatic, yet survival-oriented, and often counter-intuitive journey of Kashmiri women.

Also read: Drinking on Dal Lake isn’t just unethical—it snatches freedom, safety from Kashmiri women

The old women of ‘Naya Kashmir’

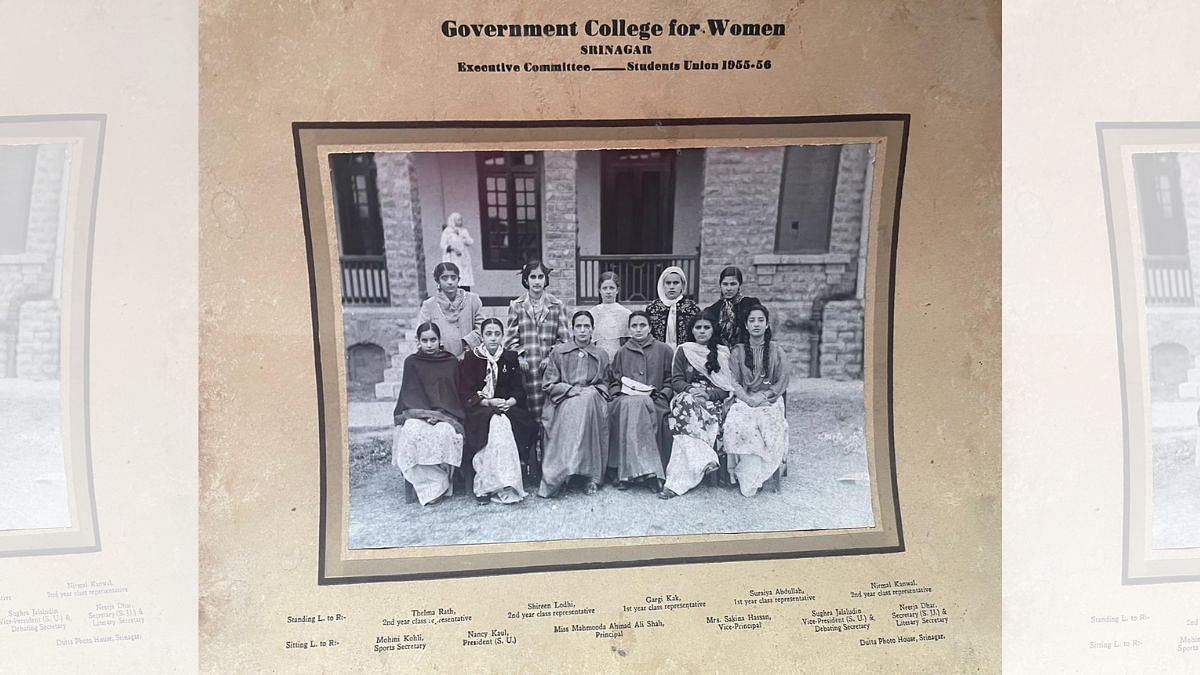

Too frail to move without help, Mattoo rings a bell to summon an attendant. As a young boy in his teens appears, she asks him to bring “the photo”. He instantly knows what she is talking about. “I show the photograph to everyone who comes to meet me, to show them what Kashmiri women looked like in the ’50s,” she said.

Within a minute, the boy reappears with a large, laminated black and white photograph, which reads, “Government College for Women, Srinagar. Executive Committee—Students Union 1955-56.”

“The principal and vice-principal were both Muslim,” Mattoo said. “And look, they were both wearing saris.” Of the 11 women in the photograph, only one has her head covered. “She is Suraiya, Sheikh Abdullah’s daughter.”

Women teaching in universities wearing saris was not an apolitical act.

“It was a function of the politics of the day, and the kind of choices women were making,” Mattoo says.

In the first few years after the Indian Independence, Kashmir witnessed what has been termed by Hafsa Kanjwal, a professor of South Asian history at Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, as “state-led feminism”.

‘Naya Kashmir’, a Soviet-style manifesto which envisioned an independent, socialist and modernising Kashmiri state, became the bedrock of this state-led feminism. Free education, abolition of zamindari and the ‘land to the tiller’ policy—the foundation of National Conference’s (NC) welfare politics, which gave Abdullah unparalleled popularity among Kashmiris—had a huge impact on women, too.

“The manifesto had a separate chapter on women. It gave several incentives for women’s education,” said Mallik. “For instance, professional colleges were to have 50 percent reservation for women, their inheritance rights were spelled out…The manifesto provided the framework within which women could flourish.”

As Kanjwal argues in an essay titled The New Kashmiri Woman State-led Feminism in ‘Naya Kashmir’, the story of the women’s movement in Kashmir is unique because there was no indigenous feminist movement in the erstwhile state. “The state was the movement,” she said.

In an essay for the book Speaking Peace, Women’s Voices from Kashmir, Mattoo wrote, “The years from 1950 to the ’70s were the kind of years when everything seemed within reach, anything possible with hard work and determination. The achievements of women during these decades were so significant that they altered the gender landscape of schools, colleges, offices, courts, police stations, hospitals, hotels and business establishments. Women were everywhere, making their mark in every field. This revolution had been brought about surprisingly, without there being an organised women’s movement in the state.”

But it was not just the formal structures of education and employment. Women’s social lives thrived, too.

“I remember post-college, we used to go to Hazratbal, eat pakodas or sit by Dal Lake, and chat for hours,” Nayeema Mehjoor, author of Lost in Terror, and one of the first female Kashmiri journalists to report on the conflict, said, filled with nostalgia. “That was our life.”

While pre-militancy Kashmir was stiflingly patriarchal—Mehjoor and her sister had to bear endless taunts from family members for pursuing education in the 1970s and 1980s—women’s lives were nevertheless vibrant, she said.

“For our class of people, social life typically centred around family and religious festivals, but it thrived,” she said. “Women would sing and dance freely during Ramzan, and the men wouldn’t mind.”

There was mobility too. “I used to meet my married sisters every day,” she added.

For the rich and the elite of society, liberalism and conservatism both were heightened.

“It was the rich—the Syeds and Khojas—whose women would wear the burqa or the hijab,” said Mallik. “The burqa had both the class and caste element…For the rest of the women, the burqa was totally alien. They were mostly peasant women, who worked on the field anyway…Burqa was unthinkable for them.”

If for a section of the elite, their status meant more restrictions, for the others, it meant more freedom.

“I remember, growing up, my mother and her friends used to go for kitty-parties to the Oberois by the Dal Lake,” said Ufair Ajaz, a third-generation owner of the family-owned Kashmir Motors. “Society was not suffocating for women at all…The years to come were a cultural shock for Kashmiris.”

“It is possible that memories of pre-militancy years are romanticised and glorified by Kashmiri men and women,” said a university professor who wished to not be named. “But psychologically speaking, that is an important collective memory of what they consider the ‘good times’.

‘The angels of death’

Until the 1980s, women of a few families which came back from Saudi would wear the burqas and hijabs. “We would think it’s some fashion they picked up from there…Nobody thought it was a religious garment for Muslim women,” Mattoo said.

But by the late 1980s, however, the association of the burqa with Islam became hard to miss.

In 1987, Asiya Andrabi, an “Islamic feminist”, and her organisation, the Dukhtaran-e-Millat, appeared on the scene. “They would be covered head to toe…You could not even see their fingers,” said Mattoo. “They started going around telling women to cover up. But who was going to listen? People used to call them malq-ul-maut—angels of death.”

“Nobody was going to take them seriously,” she said. “If not for the power of the gun.”

By 1989, militancy had decidedly struck Kashmir. What began as a militant movement for self-determination or azadi, in which hundreds of ordinary Kashmiri women participated along with men, rapidly turned into a battle of hundreds of factions subscribing to varying degrees of violence pitted against the Indian armed forces.

Before many of its participants could even fathom, their movement for self-determination had assumed meanings and implications far beyond their control or comprehension.

An unending whirlpool of violence and carnage ensued, and Kashmir’s women were at its centre.

“I was reporting for BBC Urdu, and living in London,” said Mehjoor. “Kashmir was on top of the international agenda at the time, so they sent me to Kashmir for six months in 1992 to do a 15-part series.”

“When I came to Kashmir in 1992, it didn’t look the same. Suddenly, all the women were behind the veil,” she said.

In no time, Mehjoor was to find out exactly how the change happened. “I was coming back from work one day, and a few men came in an auto and threw paint at me,” she said. “I still remember that day…I was wearing a parrot green suit with embroidery, and it was splashed with this white paint.”

Onlookers were sympathetic. But they had an advice for her—“You should wear the burqa”.

Mehjoor may have been one of the luckier ones. In the early 1990s, reports of women being killed or thrown acid at for not wearing the veil became commonplace. Shamina, a drama artist and a colleague of Mehjoor’s, was kidnapped by militants. “After three-four days, her body was found in the gutter…There was complete fear psychosis.”

“Until then, I too had been sympathetic to the cause of azadi as long as it was peaceful,” she said. “But that day I realised this is a reformation movement…They wanted to teach women a lesson.”

Cinema halls began to be vandalised. Beauty parlours were attacked. Schools and colleges burnt. Entertainment and vanity were violently crushed. “Kashmir had become unrecognizable,” Mehjoor said.

The intention was clear. It was to transform the traditional, indigenous, Sufi Islam in Kashmir into a puritanical, monotheistic Islam, which was culturally alien to the Valley, said Mallik. The women were a crucial tool in this regard.

Yet, the violent diktats to hide behind the veil were resisted by Kashmiri women. As most women who lived through those years say, within a few months, women stopped wearing the burqa—but only to rediscover it as their shield, an instrument of survival in the new, transformed Kashmir.

Forced emancipation

“Have you heard of the Ikhwanis?” asked Rubika, a 20-year-old, abaya-clad, post-graduate student in Kashmir University, her eyes peering out from between her hijab and the surgical mask covering her face.

“When my mother was a student, a bunch of Ikhwanis came and lived with them (her mother’s family) for months…You could not refuse them. In fact, you had to prepare delicacies for them,” she said. “My mother says, for many months, there was a barricade within their home.” The Ikhwanis lived on one side, and Rubika’s mother and her family on the other.

“You can only imagine what that did to the women of the house. They had to go into hiding within their own homes.”

The Ikhwanis were the controversial army of surrendered militants who had switched sides, and became informers for the Jammu and Kashmir Police in the early 1990s. With AK-47s casually draped on their shoulders, they would walk around the bazaars and streets of Kashmir in plain clothes and complete impunity. In this bloody decade, they helped the security forces break the back of militancy in Kashmir, providing inside tracks into groups they were once part of.

But accused of countless incidents of human rights abuses, rapes, and “forced love marriages”, they were also arguably the most damned people in Kashmir.

“They had many wives,” said Rubika. “They could ask for anyone’s daughter as their wife. I don’t know how my mother and her generation of women lived like this.”

For women living through the 1990s, though, it was simply their reality.

According to the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, as of 2015, between 6,50,000 and 7,50,000 Indian soldiers, paramilitary, and police were deployed in Kashmir.

Security forces, as has been recorded in several studies and books, including Speaking Peace, were widely accused of horrendous sexual crimes against Kashmiri women.

The garment, seen as an infringement of their liberty just a few years ago, was now a protective shield.

This was especially important since now, more than ever, women had to be in the public space.

“My mother tells me that during those years, her parents would always send her to fetch medicines or do bank work, and not her brother” said Rubika. “It was considered more unsafe for mamu to go out since young boys could be killed, made to disappear or roped into militancy…Sending girls was considered safer.”

Even when security forces came to people’s homes for “cordon and search” operations that are locally called “crackdowns”, the men were asked to go out, leaving the women to deal with them.

This, Mallik explains, was the paradox of the Kashmir conflict.

Women were pushed into the public domain, forced to take up traditionally masculine roles, even as their liberties shrank.

“There was a phase in 1992-1993, when there were only women on the road,” said Mehjoor. “They were going to jails to find their sons or husbands or fathers, and negotiate with the authorities. They were going to the army camps, looking for lawyers, trying to find all sorts of jobs to sustain themselves—it was a feminist revolution,” she said. “Except, it wasn’t.”

“There was no women’s movement in Kashmir to make them work and earn. They had to do it because of their political circumstances,” she added.

The initial years of the insurgency, most women recall, were particularly hard. Women, for instance, who had no experience of working outside the house, suddenly found themselves having to take up the roles of breadwinners. “They started working as maids or spies for the agencies in some cases,” said Mehjoor, who served as the chief of the women’s commission of Jammu and Kashmir until its statehood was dissolved in 2019.

After the initial years of shock, however, there was a revolution in women’s education. “It was no longer about liberating women or about their progress. Women had to be prepared to start working if their husbands or fathers died or disappeared—it was a necessity,” the professor quoted above said. “After a point, Kashmiri women did not have the liberty to be shocked by death. They had to be prepared for it.”

Yet, the anxiety about women’s safety and sexuality intensified during this period too. “During a period of conflict, women anywhere become the markers of a community’s honour,” the professor said. “This was true for Kashmir too…Women were raped and abused in large numbers in what was a symbolic emasculation of the Kashmiri men.”

According to a 2005 study conducted by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), 11.6 percent women interviewed for the study reported being victims of sexual violence since 1989.

As the external world became increasingly hostile, so did the domestic world. “If there is so much violence in the public domain, it tends to percolate into the domestic realm too,” said Mantasha Rashid, a Kashmir Administrative Service (KAS) officer, who also founded Kashmir Women’s Collective.

“During the years of militancy and counter-insurgency, cases of domestic violence against women increased significantly. As men were emasculated outside, they sought to reclaim their manhood within the precincts of the home,” she said. “But there was no one to listen to these women, doubly victimised.”

It was only in the mid-1990s that some semblance of a civil society began to develop. In 1994, for instance, Parveena Hangar, whose son had been abducted and “disappeared”, founded the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), an organisation to help “half-widows” and parents to help find husbands and sons made to disappear.

Since 2019, the organisation, Kashmiris said, has been somewhat defunct.

Religion, scooties and fashion

In the first decade of the 2000s, a scooty revolution was underway in India. In the late 1990s, TVS Motors had come up with scooters for women. Within a decade, they were all the rage. In 2009, they were selling about 25,000 scooties a month, compared to about 60,000 a month for the overall top selling scooter in India.

Ufair Ajaz, the owner of Kashmir Motors, who had just returned to Srinagar from Pune, where he was studying, wanted to bring the scooty to his own city. But he knew it was no mean task.

“I began by campaigning in schools and colleges, where we would tell young girls about mobility,” he said. “We would tell them that if they learn how to ride a scooty, they can travel without their brothers.”

Those were times when women barely even drove. Riding a scooty, for which you have to probably wear pants, was unimaginable. “Also, the spectacle of a girl riding a scooty is more in-your-face than a woman driving a car,” he said.

The campaigns were a recipe for trouble. “We started getting calls from the radicals,” Ajaz said without specifying who exactly the “radicals” were. “They would tell us, don’t create this kind of an atmosphere in Kashmir,” he said.

Like in the rest of the country, TVS Motors brought its scooty advertisements starring Preity Zinta and Anushka Sharma to Srinagar. But there was a problem. In the advertisements published in local newspapers and displayed on public hoardings in the city, Zinta and Sharma were wearing shorts.

“There was intense backlash,” Ajaz recalled. “We had to physically paint over their legs in some posters to calm people down.”

But soon Ajaz knew that he had to tweak his campaign. “I got posters of women riding scooties in Iran. They were dressed modestly, and wore a hijab…We also changed the tone of the campaign,” he said. “From focusing on women’s mobility, we pitched the scooty as a means to ensure their safety…We said that if they learn how to ride a scooty, they can come back home in time, and would not need to travel in buses jostling against men.”

They also had a new jingle: Humari Tehzeeb, Humari Pehchaan, Chale TVS Scooty ke Saath.

Within months, he had turned a corner. The J&K Bank was now giving scooty loans, and their sales were growing phenomenally—a trend still visible on the streets of Srinagar, where hijab-clad young women on scooties are a ubiquitous sight.

In what may seem as an irony to outsiders, in Kashmir, hijab is not just a symbol of religion and faith. It is often also a symbol of youth, modernity, and even fashion, especially for Gen Z. For the older women, by contrast, the now-unglamourous dupatta, with which they cover their head, still does the job.

Over the last decade or so, many observers say that the hijab has indeed become an aspirational garment for young women.

“In the 1990s, I remember my mother suddenly got a burqa when the militants started imposing it…Until then we had never had one at our house,” Shazia Manzoor, a professor of social work at the Kashmir University said.

Moreover, a lot of the young girls have no memory of the battles their mothers and grandmothers waged to resist the burqas in the 1990s, added Manzoor.

Mattoo agreed. “My own students still don’t wear the hijab, but their daughters want to wear it,” she said. “What can we say?”

The phenomenon, Mallik said, might have little to do with the conflict though. “The hijab in Kashmir is more a product of globalisation than conflict.”

In his book Globalized Islam published in 2002, Olivier Roy theorises the phenomenon. The spread of Islam around the globe, he argued, has blurred the connection between religion, a specific society, and a territory, and given rise to a somewhat decontextualised Islam in a bid to create a universal religious identity.

Strategic forgetfulness

In April 2017, an image, perhaps the first of its kind, of a young girl in her teens dressed in a blue salwar-kameez, pelting stones at the security forces in Kashmir’s Pulwama district went viral. Overnight, Afshan Ashiq, the young girl in the picture, became the new face of the disenchanted Kashmiri youth.

“The policeman made objectionable remarks about the girls. I could not bear it,” she later told The Hindu, quickly adding that she “does not want to look back to the episode any more… It doesn’t make me happy.”

Ashiq, a football player, soon became the captain of the first ever Jammu & Kashmir women’s State football team. In no time, she was turned into an icon for the other side.

Her journey mirrors that of several young girls, who have experienced the turmoil of 2016 when the valley was up in flames after the death of militant Burhan Wani, and the communication blackout in 2019. But for now, they are only too keen to forget the past, and make sure it never happens again.

“We are the Gen Z, we don’t want anything except to be treated normally like other Indians,” said a young girl, a student at the Islamic University of Science and Technology (IUST) in Awantipora.

“We don’t talk about those things anymore even though we remember everything…it is in our flesh and bones,” she said, speaking of the decades-long conflict. “In many ways, the conflict is still not over…But see, as young people, a phone is mandatory for us. In 2019, when there was a complete blackout, it was a nightmare. Why would we want to repeat that? So, it is just better to sit down and study even if it means to never speak up.”

Like a majority of her colleagues in the university, the young girl wears the hijab. “There is nothing political about it…it is simply a religious obligation for us,” she said. “I don’t understand why the hijab is always under the scanner. Does everything we choose have to have some political connotations?”

For many young Kashmiri girls like her, the choice is between choosing a career or speaking their minds. For now, it seems to be made.

But in Kashmir, even making that choice is a privilege—one that few Kashmiri women have.

In Anantnag-Bijbehara, as election campaigns are in full swing, with a candidate making a speech, an old woman quickly steps out of her home and watches eagerly at the politician trying to make an eye-contact.

Jostling for space, she manages to reach the candidate’s cavalcade and says, “I want to whisper something in your ears”. As the crowd looks on, she tells the candidate that her grandson is languishing in the jail. “Ek baar bas usko bahar karwa de, mujhe aur kuch nahi chaiye (if you could just get him released, I don’t want anything else),” she tells her.

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: Gadar, Roja, Dil Se, Lakshya—Indian millennials’ memory of Kashmir was shaped by movies