BJP concentrated its efforts on attracting non-Jat and OBC voters, which seems to have worked effectively. The party gained more traction than the Congress among Brahmins, Punjabi Khatris, Yadavs and non-Jat Dalits, which helped secure the party’s third consecutive victory in Haryana.

The survey shows that the Congress managed to rally a significant portion of Jatav voters among Dalits, a group closely associated with senior Congress leader Kumari Selja. Additionally, it secured support from Muslims and Sikhs, who make up about 7 and 4 percent of the total electorate, respectively.

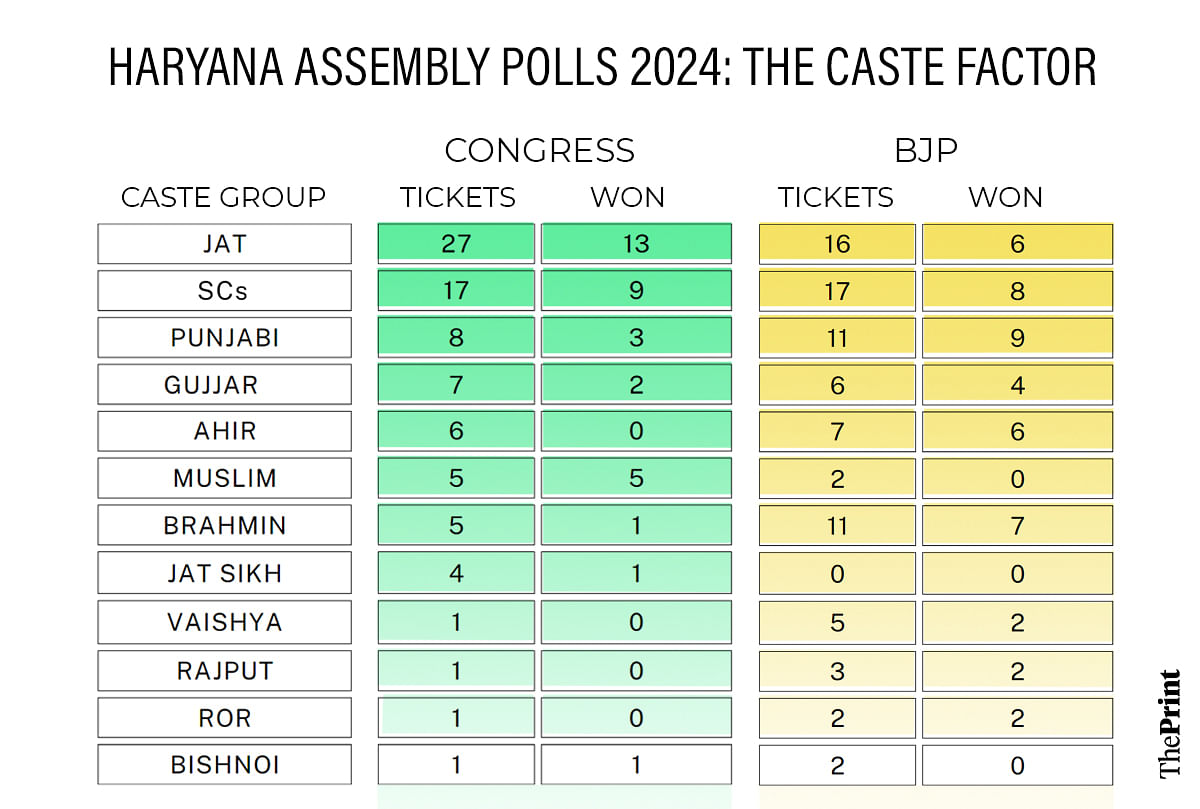

The BJP’s Punjabi and Ahir candidates had the best strike rates. Among Punjabis, the Congress had fielded eight candidates and won three seats, whereas the BJP scored nine wins with 11 tickets.

In the Ahir community, the Congress had fielded six candidates, but they all lost. The BJP’s seven Ahir candidates won six seats.

According to the CSDS-Lokniti survey, 68 percent of Yadavs voted for BJP, compared to 25 percent for Congress, which resulted in the latter’s dismal performance in the Ahirwal belt. Punjabi Khatris —the community former chief minister Manohar Lal Khattar belongs to— largely voted for the BJP. The survey shows that 68 percent of voters in the group picked BJP, while 18 percent supported the Congress.

From the announcement of candidates to the election campaign, the Congress primarily focused on the 22-25 percent Jat and 20-22 percent Scheduled Caste voters. In contrast, the BJP, in line with its non-Jat strategy, focused on the 30-32 percent OBCs, 9-10 percent Punjabis and 8-9 percent Brahmins.

A key highlight is that the BJP won four out of six seats in Sonipat district, which is part of Haryana’s Deswali belt, considered a stronghold of former chief minister and Congress leader Bhupinder Singh Hooda. BJP bagged the Kharkhoda and Gohana seats here for the first time, which it hadn’t won even during the Modi wave in 2014 and 2019. The party also won the Rai and Sonipat seats.

BJP’s rebel candidate Devendra Kadian won the Ganaur seat, while Congress managed to win just one seat here.

Also Read: Behind Congress’s shock defeat in Haryana, rebels, Independents & INDIA bloc allies

‘Other groups alienated by the Congress’s Jat-centric strategy’

In 11 assembly seats where Congress had fielded Jat candidates, BJP countered with candidates from other communities. The latter gave tickets to Brahmin candidates in four constituencies, Vaishya candidates in two, and one each to the Bishnoi, Bairagi, Gujjar, Saini and Sikh candidates. Of these, BJP won eight.

The Congress’s Jat candidates managed to win only three seats. BJP’s non-Jat strategy worked well in Jat-majority constituencies, like Uchana, Gohana and Palwal.

With respect to other parties, both Indian National Lok Dal (INLD) MLAs are from the Jat community. Of the three Independents this time, two belong to the Jat community, too.

Both the BJP and the Congress had fielded 21 OBC candidates each. Of the 17 OBC MLAs who have been elected, 14 are from BJP and three from the Congress. In the Rania seat, where both parties had fielded OBC candidates, the INLD’s Arjun Chautala—a Jat—won.

According to Kushal Pal, a political science professor and principal of Indira Gandhi Government College in Kurukshetra’s Ladwa, the Congress inadvertently did what the BJP had done in 2014 and 2019—polarisation of votes along caste lines between Jats and non-Jats—and this provided the BJP a well-prepared pitch to bat on.

“The Congress campaign was so Jat-centred that several candidates openly addressed Hooda as the future CM of Haryana. Congress MP Jai Parkash had said on stage several times that Hooda would return as CM. The media did the rest by explaining how 72 of the 90 seats have been given to Hooda’s people,” Pal told ThePrint.

Additionally, the issues raised by senior Dalit Congress leader Kumari Selja about how Hooda loyalist Jassi Petwar was given a ticket in Narnaund—ignoring her associate Dr Ajay Chaudhary—as well as a casteist remark allegedly made against her by a party worker, were left unaddressed by the party’s top leadership in the state. “Selja didn’t campaign for a fortnight till Rahul Gandhi himself intervened and asked her to attend his rally. When Rahul tried to make Selja and Hooda shake hands, the two leaders were hardly able to betray the discomfort on their faces,” said Pal.

He added, “This gave the BJP the ammunition to use against the Congress, which it used to the hilt by highlighting incidents in Mirchpur and Gohana during the Hooda regime, where Dalits were targeted by the dominant Jat community.”

Pal listed several moves that made the Congress’s campaign appear Jat-centric: the grand reception accorded to Vinesh Phogat by Congress workers led by MP Deepender Hooda while the BJP kept its distance; visuals of Rahul Gandhi holding hands with Bajrang Punia and Phogat; Phogat getting the ticket from Julana; and having Punia campaign for Congress candidates.

Even Rahul Gandhi’s visit to the Karnal residence of Amit Mann, who had been injured in a truck accident in the US, which was intended as a noble gesture, also led to the campaign being viewed as Jat-centric.

“When a person, leader, or political party begins to show excessive inclination and proclivity towards a community considered dominant in society, the other backward and neglected sections do not just distance themselves from that person, leader or party, but also quietly unite against them,” Pal said.

“This is a common phenomenon, and the results of the Haryana elections reflect this to some extent. Before the elections, Congress had begun showing a clear inclination towards the Jat community, which made the OBC, Brahmin, Punjabi, Vaishya, and to some extent, SC communities, feel alienated.”

He said that the Congress’s politics instilled a sense of insecurity among these groups. The BJP’s think tank sensed this and continually raised the issue of Selja being disrespected and neglected. As a result, a large portion of these communities, except the Jats, set aside their resentment and aligned with the BJP.

Congress candidate and former MLA Shamsher Singh Gogi, who lost from the Assandh seat in Karnal, also cited this reason for the party’s defeat.

Congress strategists, especially the Hooda camp, could not come up with a solution to the Selja issue in order to stop the damage. “To some extent, their overconfidence was also responsible. Now, the results are evident,” Gogi remarked.

According to Pal, even statements by Congress leaders, like Neeraj Sharma (Faridabad), Kuldeep Sharma (Ganaur) and Gogi (Assandh), worked against the party as the BJP was able to compare the recruitments under its rule without “kharchi and parchi” to the erstwhile Hooda-led government’s jobs, allegedly given away on recommendations and bribes.

Ashutosh Kumar, a political science professor from Panjab University, Chandigarh, said that the Hooda regime from 2005 to 2014 was closely associated with the Jat community, and in the run-up to the election, almost every candidate from the Hooda camp was projecting him as the future chief minister.

“This may have gone against the Congress through the consolidation of non-Jat votes for the BJP. However, this will have to be verified from some authentic election data,” he added.

Kumar said that it is important to bear in mind that in any election, the BJP starts with an advantage, given its human and material resources and the popularity of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“To say that the BJP’s victory is astonishing will be incorrect, but winning an election after being in power for 10 years is something remarkable,” Kumar said.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Behind BJP’s historic 3rd term in Haryana, grassroots-level cadre, RSS support & Congress hubris